Hollywood’s most iconic comedy almost starred Charles Manson as a high school student on an alien-hunting adventure, a revelation that exposes how drastically different entertainment could have been.

The Manson Script That Never Was

In the early 1970s, National Lampoon magazine—a publication built on irreverent humor and boundary-pushing satire—aimed to break into filmmaking. Co-founder Doug Kenney, struggling with divorce and drug addiction, received a creative lifeline from publisher Matty Simmons: develop a movie project.

Kenney partnered with Harold Ramis, and together they conceived Laser Orgy Girls, a script that weaponized Charles Manson’s notoriety as dark comedy fodder. The premise imagined Manson as a high school student pursuing wild sexual adventures and alien encounters in the desert, framed as absurdist satire.

The script represented peak 1970s Lampoon excess—an era when the magazine’s writers believed shock value and taboo subjects were fair game for comedy. Manson’s 1969 Tate-LaBianca murders had cemented his status as America’s symbol of hippie-era horror. Lampoon’s satirical instinct was to deconstruct that mythology by reimagining Manson pre-cult, stripping away the terror and replacing it with ridiculous sexual hijinks and sci-fi absurdity. It was conceptually audacious, commercially suicidal, and destined for obscurity before production ever began.

The Producer’s Veto That Changed Comedy

Matty Simmons, the financial gatekeeper, took one look at Laser Orgy Girls and rejected it. The high school setting, combined with explicit sexual content and direct Manson references, created a liability nightmare. Simmons wasn’t being prudish; he was being pragmatic. No studio would touch it. No theater chain would book it. The film industry in 1976 had limits, and Simmons recognized them. He mandated a complete creative reset: abandon Manson, move the setting to college, and find a new angle.

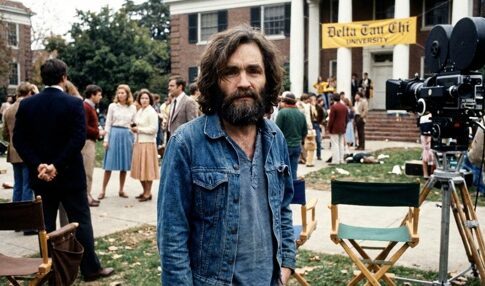

This rejection became the hinge point of comedy history. Kenney and Ramis, rather than fighting Simmons’s veto, pivoted. Chris Miller, a Lampoon writer with real Dartmouth fraternity experience, joined the project and infused it with authentic frat stories. The college setting allowed the sexual content to feel less predatory and more peer-driven. The Manson references evaporated entirely. What remained was the anarchic spirit of Lampoon’s humor, now channeled through fictional Delta Tau Chi fraternity members at Faber College, defying Dean Wormer. The script that emerged bore almost no resemblance to its predecessor, yet retained the irreverent DNA that made Lampoon distinctive.

From Obscurity to Blockbuster Dominance

Animal House premiered on July 28, 1978, directed by John Landis and starring John Belushi. The film grossed $141 million, a staggering sum for its era, and defined the gross-out comedy genre for decades. It launched careers, inspired countless imitators, and became cultural shorthand for youthful excess and institutional rebellion. The film’s success spawned sequels, influenced movies like Old School and American Pie, and established National Lampoon as a powerhouse creative force in Hollywood.

The irony cuts deep: a script born from dark Manson satire became a celebration of harmless collegiate anarchy. Simmons’s commercial instinct proved correct. Audiences embraced the frat chaos but would have rejected—or worse, boycotted—a film that made comedy from a mass murderer’s teenage years. The buried Manson origin reveals how market forces shape cultural output. Edgy concepts survive only when they’re sufficiently abstracted from their disturbing source material.

Doug Kenney, the original architect of the Laser Orgy Girls, never fully capitalized on Animal House’s success. He struggled with the same demons that drove him to dark comedy in the first place, and died by suicide in 1980. Manson himself lived until 2017, dying in prison, never knowing he’d nearly starred in Hollywood’s most iconic comedy. The story exists now only in retrospectives and film histories, a footnote to a cultural phenomenon that might have been unthinkable.

Sources:

The Original Animal House Script Based on Charles Manson

Charles Manson Family: Scenes from Their Desert Hovels

The Triumphant Disgrace of Animal House

Mass Murderer Charles Manson Lived in Indianapolis at Age 14